How Expressive Are Invariant Graph Networks? (2:2)

Haggai Maron and Yaron Lipman, Weizmann Institute of Science

This is the second post summarizing the main ideas and constructions in a series of three recent papers (Maron et al., 2019 a,b,c). In this post we focus on (Maron et al., 2019b) that was presented at ICML 2019 and an additional technical report (Maron et al., 2019c).

Up until now, we have discussed a principled way of constructing invariant graph networks. Our next step is analyzing the expressive power of these models. Expressivity of graph neural networks is studied from different perspectives (Chen et al., 2019). In (Maron et al., 2019a,b) we studied the question: what kind of functions can IGNs approximate? More recently, in (Maron et al., 2019c), we study the capability of IGNs to discriminate non-isomorphic graphs. When we say that a model can discriminate between two non-isomorphic graphs $G_1,G_2$ we mean that there is a set of parameters for the IGN model that results in a function $f$ with the property $f(G_1)\neq f(G_2)$. Recall that by construction $f(G_1)=f(G_2)$ if $G_1,G_2$ are isomorphic.

Function approximation point of view

In (Maron et al., 2019a) we proved the first result of this kind: $2$-IGNs, i.e., IGNs with a maximal tensor degree of $2$, can approximate any message passing neural network to an arbitrary precision (on compact sets). Message passing neural networks (Gilmer et al., 2017) are very popular models for learning graph data which currently provide state of the art results on various graph learning benchmarks.

In (Maron et al., 2019b) we further generalize this result and show that IGNs are universal when using sufficiently large tensor order $k$. Universality means that $k$-IGNs can approximate any continuous invariant function to an arbitrary precision (on compact sets). The main idea is showing that IGNs can approximate a set of generating invariant polynomials (see theorems (1)-(2) in (Kraft and Procesi, 2000)). An alternative proof was recently suggested in (Keriven and Peyré, 2019).

Graph discrimination point of view

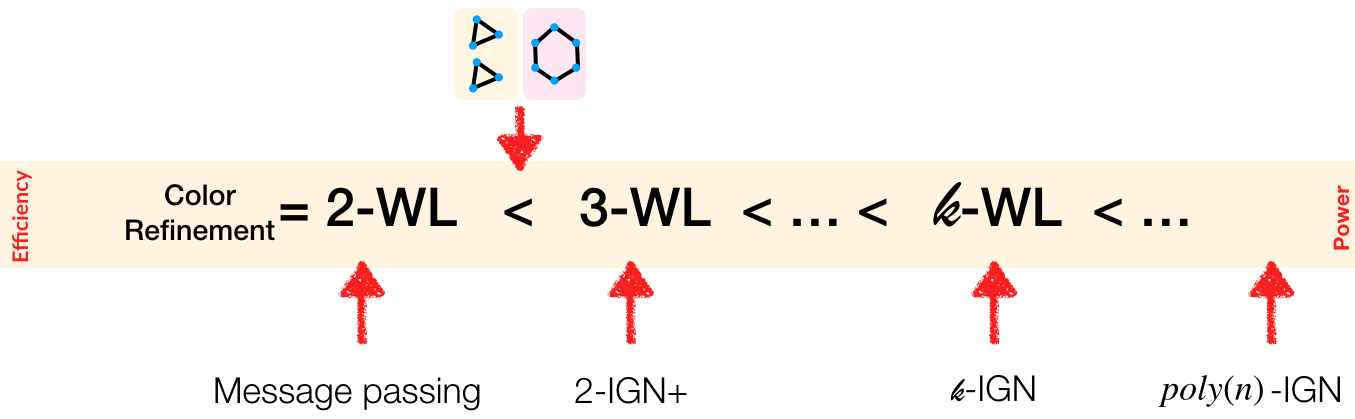

In (Maron et al., 2019c) we show that $k$-IGNs are tightly related to a hierarchy of graph isomorphism tests called the Weisfeiler-Leman (WL) hierarchy (see (Morris et al., 2019) for an overview). The WL hierarchy defines an algorithm, called $k$-WL, for every $k \in \mathbb{N}$. The first member of this hierarchy, $1$-WL (also called the color refinement algorithm) iteratively generates node features (colors) by aggregating features of neighboring nodes. When this process reaches a steady state (i.e., same color nodes are not colored by different new colors), the histogram of these colors serves as a global graph descriptor that can be compared to descriptors of other graphs in order to test isomorphism. For $k>1$, $k$-WL is defined in a similar way where instead of node features node $k$-tuples features are used. It can be shown that for any $l>k$, $l$-WL is strictly more powerful than $k$-WL, meaning it can discriminate a broader set of non-isomorphic graphs.

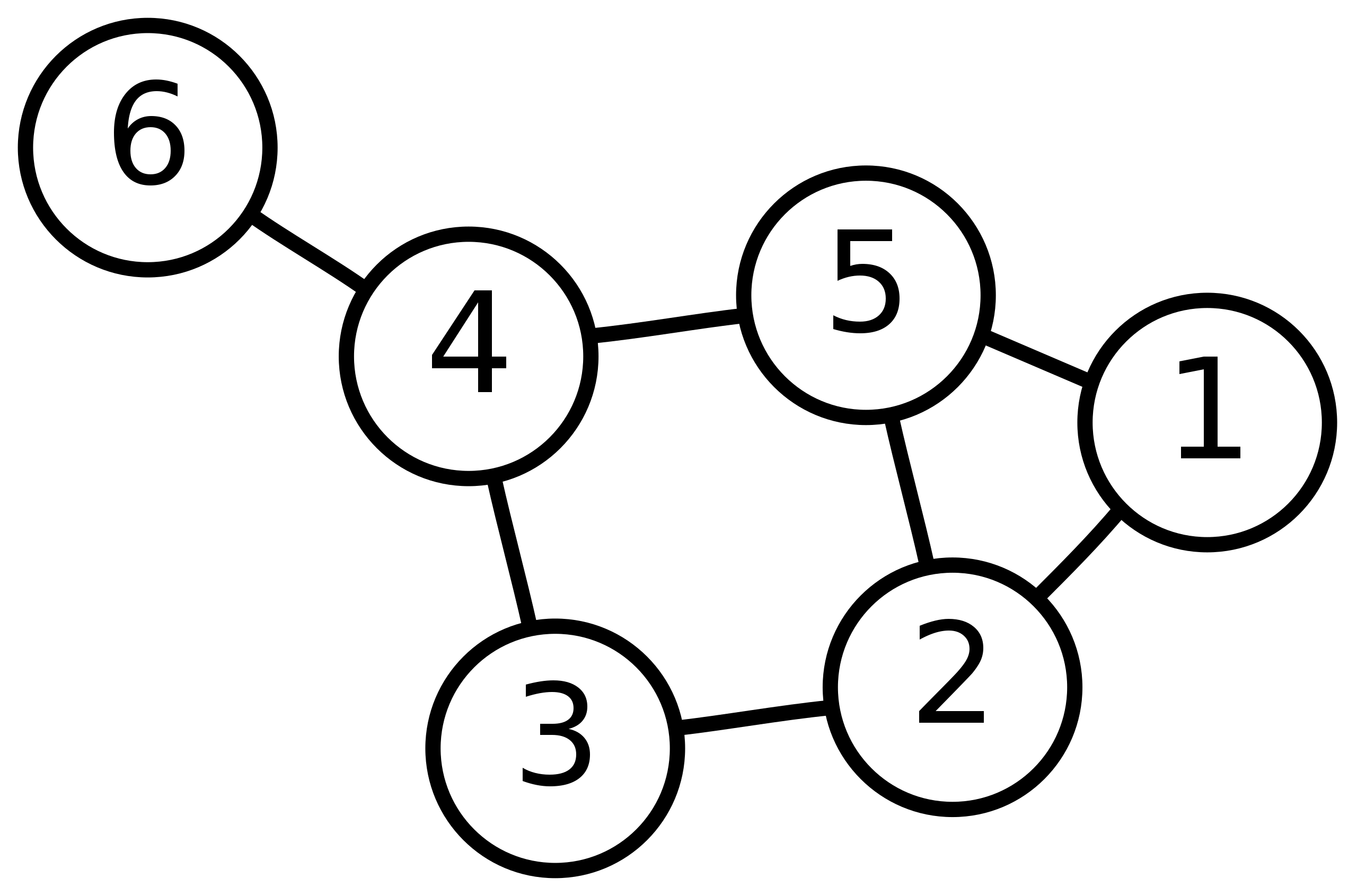

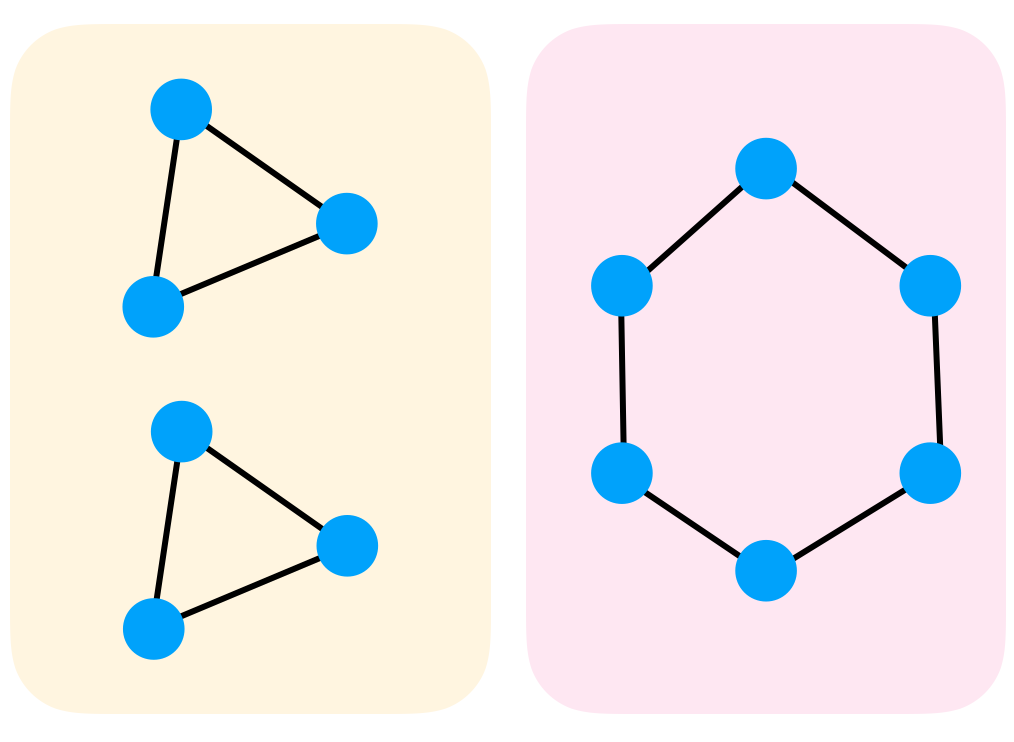

This direction follows the prominent works of (Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019) that prove that message passing neural networks can discriminate between non-isomorphic graphs as well as the $1$-WL. Sadly, $1$-WL is not strong enough and, for example, cannot discriminate regular graphs such as the pair of graphs in the figure. (Morris et al., 2019) also suggests a message passing algorithm directly on $k$-tuples to achieve $k$-WL discrimination power. In (Maron et al., 2019) we prove that $k$-IGNs can discriminate graphs at least as good as the $k$-WL algorithm, for every $k$. For example, $3$-WL already discriminates the pair of regular graphs mentioned above.

A simple and expressive variant of IGNs

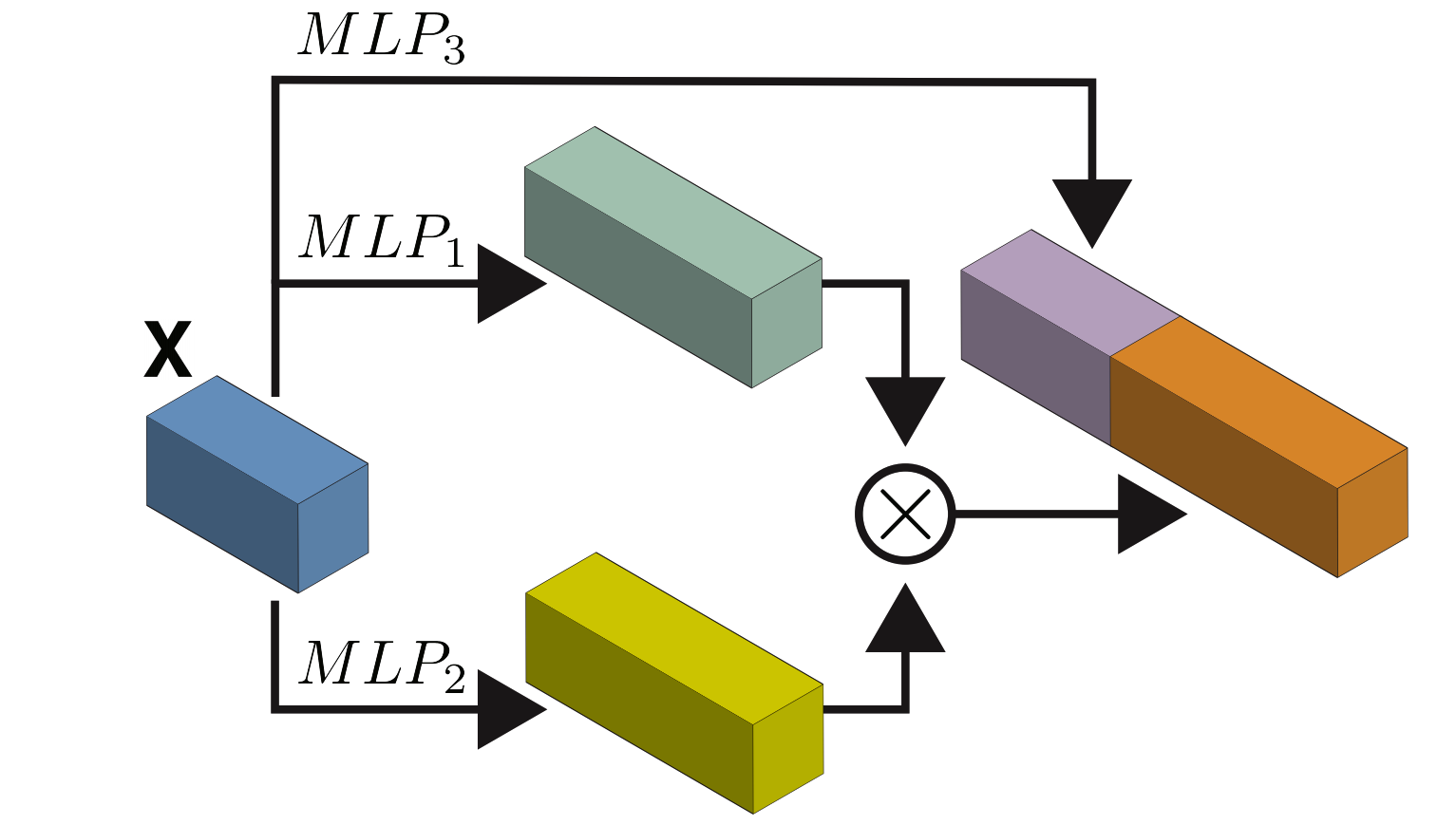

The main drawback of $k$-IGNs is the fact that one needs to store and process $k$-order tensors, limiting its applicability. In (Maron et al., 2019c) we suggest a variant of $2$-IGNs that is at least as expressive as the $3$-WL test. Hence, strictly more expressive than message passing models. This variant, which we call $2$-IGN+, consists of building blocks as follows (see inset): Each block is constructed with 3 different MLPs applied to the feature dimension of the input $2$-tensor. The outputs of two of these MLPs are multiplied feature-wise using regular matrix multiplication, while the output of the third MLP is concatenated to this product output. One of the main strengths of this model is its simplicity: MLPs on the feature dimension can be implemented by simple $1\times 1$ image convolution, while matrix multiplication is a basic operation that is supported by all deep learning frameworks.

Note that applying an MLP to the feature dimension can be seen as a particular simplified instance of IGN, using only a single linear equivariant operator, namely, scaled identity. When the feature dimension is one, scaled identity is a linear operator that takes as input $\mathbf{X}$ and outputs $\mathbf{wX}$, $w\in\mathbb{R}$. When the feature dimension of $\mathbf{X}$ is greater than one, $w$ becomes a matrix that is applied to the feature dimension.

Let us provide some intuition as to why matrix multiplication improves expressiveness. We will do that by showing matrix multiplication allows this model to distinguish between the two regular graphs discussed above, which are $1$-WL (and $2$-WL) indistinguishable. Consider the case the input tensor $\mathbf{X}$ representing a graph $G$ holds the adjacency matrix. We can build a network with 2 blocks computing $\mathbf{X}^3$ and then take the trace of this matrix (using the invariant layer). Recall that the $d$-th power of the adjacency matrix computes the number of $d$-paths between vertices; in particular, $\text{trace}(\mathbf{X}^3)$ computes the number of cycles of length 3. Counting shows the right graph has 0 such cycles while the left graph has 12.

Summary of the IGN expressiveness

The following figure illustrates the expressiveness results for IGNs. It provides an overview of the main tradeoffs between efficiency and approximation power.

Bibliography

(Chen et al.), 2019 Chen, Z., Villar, S., Chen, L., and Bruna, J. (2019). On the equivalence between graph isomorphism testing and function approximation with gnns. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.12560.

(Gilmer et al., 2017) Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O., and Dahl, G. E. (2017). Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1263–1272.

(Keriven and Peyr´e, 2019) Keriven, N. and Peyr´e, G. (2019). Universal invariant and equivariant graph neural networks. CoRR, abs/1905.04943.

(Maron et al., 2019a) Maron, H., Ben-Hamu, H., Shamir, N., and Lipman, Y. (2019a). Invariant and equivariant graph networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

(Maron et al., 2019b) Maron, H., Fetaya, E., Segol, N., and Lipman, Y. (2019b). On the universality of invariant networks. In International conference on machine learning.

(Maron et al., 2019c) Maron, H., Ben-Hamu, H., Serviansky, H., and Lipman, Y. (2019c). Provably powerful graph networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

(Morris et al., 2018) Morris, C., Ritzert, M., Fey, M., Hamilton, W. L., Lenssen, J. E., Rattan, G., and Grohe, M. (2018). Weisfeiler and leman go neural: Higher-order graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.02244.

(Xu et al., 2019) Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J., and Jegelka, S. (2019). How powerful are graph neural networks? In International Conference on Learning Representations.